Captain

Martin Hewitt

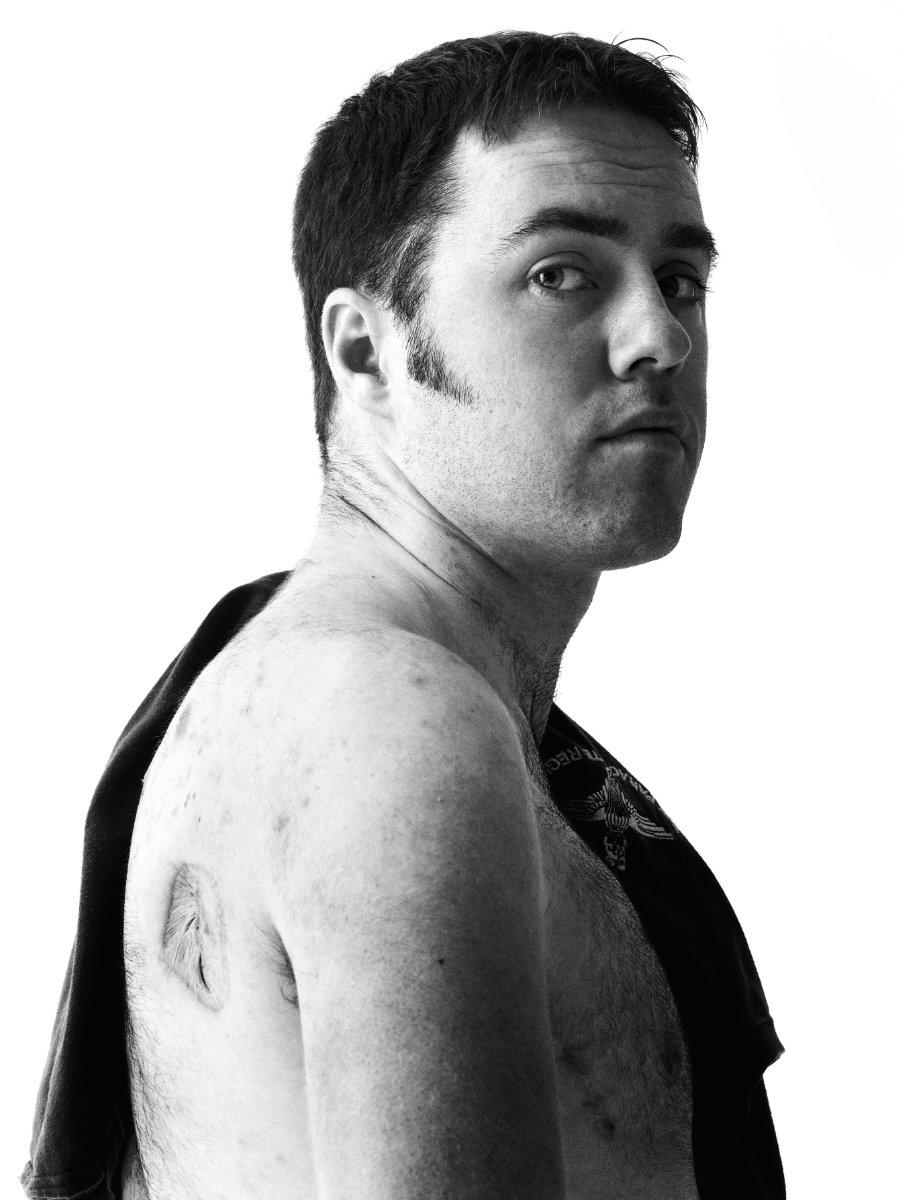

I’m a serving officer in Her Majesty’s Parachute Regiment. In Afghanistan in 2007, I was shot through the shoulder, injuring my brachial plexus. The bullet collapsed my lungs, severed the artery, severed the nerves, shattered the scapula and then left my body.

The day it happened, we were in a firefight with an enemy force and I was leading the attack. I was moving forward towards the enemy when the bullet struck. I was hit by a 7.62 long round, from a PK machine gun. The velocity was great, which probably saved my life—luckily, the bullet went straight through and didn’t deviate. Had it done so, or hit any major organs, I would’ve been gone.

When something like this happens, we go through an immediate procedure that we call Standard Operating Procedure. We try and push the enemy back and get them out of the picture, and we then try to extract ourselves from the area. I maintained command of the situation until another Commander could come in and take over the Contact Battle. I then concentrated on getting out alive.

Luckily I had a fantastic team around me that day. I had a significant amount of blood loss because of the arterial bleeding so I was completely relying on my team to get me out of there. They managed to stem the blood flow to some degree within the first twenty minutes and the support services we had were extremely effective: I was taken off the ground within 28 minutes of being shot. I received two life- saving operations within an hour and I was flown back to the UK within seventeen hours.

When I was in hospital I was told by the doctors that they had treated six other soldiers who had been shot in the brachial plexus region, severing the brachial artery, and they had all died. I was the first one that they were aware of who had survived. That was said at the time and many have said so since, so I was extremely lucky.

The injury originally meant that I was completely paralysed from the shoulder down and I couldn’t move the arm at all. But thanks to a great amount of work and some fantastic physios at Headley Court, we got a great deal of the passive movement back – passive movement is somebody else moving your limb around for you. It’s just down to consistency: you have got to do the exercises that they give you and it hurts, but you’ve got to take that pain and you’ve got to go through that motion to ensure that you maintain what function you can in the limb. It’s a fine balance between protecting the injured area and maintaining the range of movement.

Through the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in Stanmore, I’ve received a series of operations, some of which were exploratory in nature, to try and see what exactly they could do to regenerate some nerves. I’ve had a few nerve grafts, some of which have worked, some of which unfortunately haven’t. I’ve now got a little bit of bicep function back. The scar down the length of my arm is from the initial operation done in Camp Bastion in Helmand Province. That was to extract veins because the bullet severed the artery. So they extracted veins from the forearm region to reconnect the blood flow by means of a vein graft. I then had one or two nerve grafts, the first one of which was from the left sural nerve, which is in your calf, into the radial nerve, which is in your bicep, and that has generated some bicep contraction back.

Since getting shot I have become involved with a Ministry of Defence initiative called Battle Back, which uses adapted adventurous training and sport as part of the rehabilitation process. Within a year I managed to get onto the British Disabled Ski team and I’ve been racing internationally and professionally as an Alpine adapted ski racer for two years. Last year, I got involved with a charity expedition called Walking with the Wounded. We aimed to make a world first attempt on the geographic North Pole and we had Prince Harry on board as our Patron. The team was made up of four wounded guys, the two founders of the charity and a professional guide. Literally a month ago yesterday, we were standing on the geographic North Pole and we made history. We became the first amputees ever to walk to the North Pole unsupported.

I am now in the process of leaving the Army. I’m still maintaining the ski racing but I am going to have to reduce my commitments in that respect as the adventure side of what I do is taking over now. Working with the charity, I’m looking to put disabled soldiers from different nations into hostile environments and demonstrate what can be achieved post-injury with the right team—that you can move on, that life carries on and you can go on to achieve almost anything. Ideally one day, we want to get the Norwegian, Canadian, American and British teams to race against each other.

Without any shadow of a doubt, I’ve changed. I think that anybody who makes the transition from the military into society again does have to make a significant transition, and the change happens in many ways.

The Military is an all-encompassing way of life, it really is, especially with the Parachute Regiment. That has an impact on your psyche, your personality, your character and when you come out of that you almost calm down a little bit and you go through this reintegration process. I think I’ve probably chilled out a little bit more now, and I’m probably a bit more relaxed—I’ve got to be because I have to be more patient.

The long and short of it is that I haven’t got the use of my right arm. And that means, whilst I can adapt and I can improvise using technology and adapted kit to overcome the challenges it gives me, I am still missing a right arm. I am therefore slightly inefficient at certain things, which means you’ve got to calm down and be more patient. If you’re not, you’ll drive yourself into the ground through frustration. So I’ve definitely relaxed a bit more and I’m now focused on other things.

I was working hard with the Military—you get given quite a lot of responsibility at a very young age. I was 26 when I got shot and I commanded over forty British soldiers and over 100 indigenous soldiers with a budget that ran into hundreds of thousands and millions, which not many people get to do at the age of 26. Now I’m in the process of trying to raise two million pounds for charity and trying to represent my country at international level—completely different things. Hopefully we’ll utilise the focus that soldiers have into new areas and carry on achieving our goals. That’s the plan. I’ve got to try and make it work now.