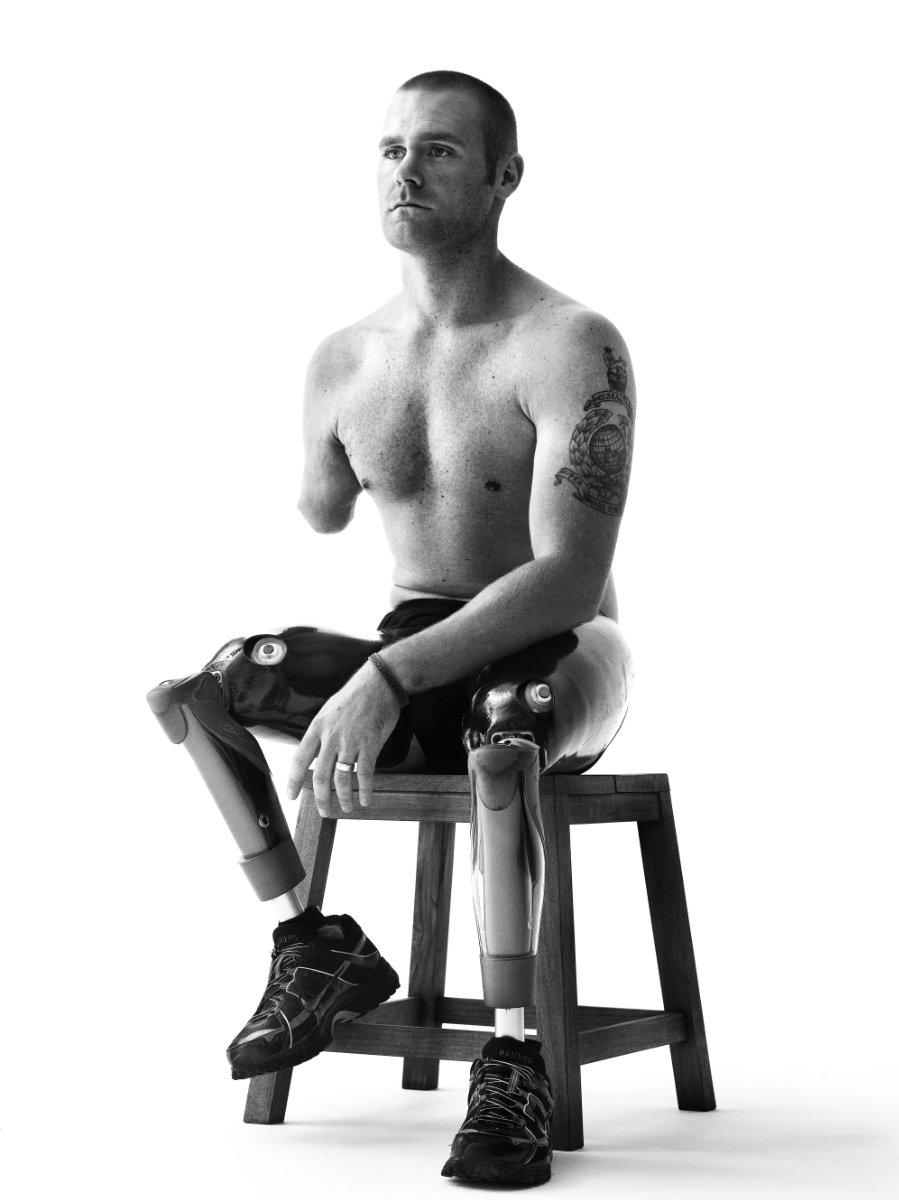

Marine

Mark Ormrod

I was deployed to Afghanistan in September 2007. My role as an infantryman was to dominate the ground around our area of responsibility and take the fight to the enemy. I was injured on Christmas Eve. We had been tasked with another foot patrol—it was more of a patrol to keep momentum going, a show of presence. We came to the end of the first leg of the patrol, and we were ready to come back into the camp. I was getting onto my stomach to get into a fire position, so I could give cover to the other guys, when I stood on and detonated an IED. It created a huge cloud of sand and dust, so I couldn’t initially see anything, but I could hear everything that was going on. My initial thought was that we’d been attacked, so straight away I was thinking, “Let this dust settle and find where we were attacked from and then start fighting back.” But then I realised what had happened to me. I’d sustained severe injuries to both my legs and my right arm, which were later amputated.

I didn’t initially feel pain. Your adrenalin spikes so high, that’s how your body deals with the level of trauma at the time. I felt an intense throbbing, like an intense pins and needles, all through my limbs. But by the time the medic got there, about ten minutes later, it was starting to hurt a lot. He gave me pain relief and stemmed the bleeding with tourniquets. He got me stable so I could be evacuated from the minefield to safety.

A lot of stuff goes through your head in a short amount of time. My first thought was of my three-year-old daughter back at home in the UK. If I survived this, would I able to be a dad? Would I be able to pick her up from school or would I shy away because she may get picked on because of how I looked? I felt a lot of guilt because of that. All of this went through my mind within seconds, as soon as I realised the extent of my injuries. Then more guilt followed because, in my mind, I had put the rest of my Section in immediate danger. If the incident had been followed up by a small-arms attack, people could have been killed and I would have blamed myself.

And anger as well, you get it drummed into your head when you go through Royal Marines training that you’re elite, you’re the best of the best, you can take on any enemy and come out on top. So to think I’d just been beaten by a lump of metal in the ground annoyed me and made me quite angry.

Once I was casevac’d from the minefield, I was taken down to a vehicle that was waiting for me. I was put in the back and the Sergeant Major was driving as fast as he could, which was throwing me all over the place. I remember that, being bounced all over the place and getting a lot of pain in my neck. The doctor actually fell out of the back of the vehicle going up a hill, but we had to leave him because we were nearly back into camp. The last thing I remember was feeling the sandstorm the helicopter blades created as it was coming down, and the heat that came out of the exhaust pipe. I blacked out then. When I started to fade, I thought I was dead and that was it. The weird thing was that I felt really calm. I thought, this isn’t a bad way to go, it’s quite honourable doing something for my country, this is me, this is my personality, I’m happy with that.

Within 24 hours of the explosion, I was in Selly Oak, Birmngham. It was Christmas morning when my family came to the hospital, but I don’t remember that. When I woke up after three days in a coma, I proposed to Becky, my girlfriend. I couldn’t see anything, I couldn’t look at her, but I could hear her. She had to ask me several times, because I was so weak that I couldn’t say things properly. When she said the answer was yes, I just smiled and then I passed back out again.

The first week in hospital was quite strange. I was on a lot of pain medication. As they weaned me off the medication, I was hallucinating a lot and initially I thought I’d only lost some fingers on my right hand, because I remember having an itch on my chest and relieving it with my right arm. Then one day I pulled my arm up from under the quilt and started laughing. The nurse asked why I was laughing, and I said, “I’ve been hallucinating all week and now this medication has made it look like my arm has come off!” Then I looked at her and that’s when I realised it was actually missing above the elbow, it wasn’t just fingers. I guess that’s the power of the mind. I was relieving itches on my body with an arm that I didn’t have.

Pretty much from the minute I woke up, because I was OK with what had happened, my family were OK with it. If I had woken up, freaked out and started crying, that would have had an impact on them. Everyone was strong for everyone else. From day one, I just thought, “OK, this has happened, let’s get on with it.”

I was in Selly Oak for six weeks and then I went to Headley Court to start rehab. There’s only so much time that you can stay in bed without going stir crazy. You can feel yourself getting stronger every day. It gets to a certain point where you get the itch and want to start doing stuff. At Headley Court, you have eight hours a day to do stuff, so it was a great motivator. The biggest challenge for me was learning to walk again. I was at the peak of my physical fitness when I got injured and it doesn’t matter how fit, or strong, or how tough you are, this whole prosthetic thing is a completely different ball game. You could be an Olympic athlete and you would struggle initially to use prosthetic legs, to learn the new techniques and to get your body used to using that kind of energy. So that initially was really, really tough.

Walking eight metres would wipe me out, I’d have to stop, rest, go to sleep for a bit. But it’s the same as anything: the more you do it, the stronger you get, and you push yourself a little bit more, you get used to it, your body gets used to it. Now, I can walk around all day long.

The worst thing for me was the way I looked. I was six foot two before the accident, weighed about sixteen stone; I was always with the boys working out and keeping fit. In hospital, my weight dropped to under ten stone. I remember after I left the hospital, we were going to the flat where my family and Becky were staying. I wheeled past a mirror, and saw what I looked like for the first time. I broke down then and cried a little bit because I didn’t like the way I looked. But it also fired me up to get back in the gym and to get stronger, to heal faster and to just start walking again and to get back to normal. It also really helped to go through rehab with other guys— all that constant challenging of each other and wanting to push each other, it helps you make progress.

I went into Headley Court at the beginning of February 2008 to start rehab, and the nurses and doctors were also aiming to get me to a position where I could go home for a bit of down time. Luckily for me, Norton House opened just after I arrived at Headley, sponsored by the charity SSAFA. Up to that point, me and my family and Becky had been staying in a welfare flat, or in hotels. But now we had this incredible mansion all to ourselves pretty much for a month, where I could stay at weekends. That clinical hospital environment can be quite depressing and to get a bit of normality back—have a takeaway, a few beers, watch a DVD—really helped. Being there was also a chance to test things out, as I was in a wheelchair. Everything at that point was learning, from opening the kitchen cupboard to making a cup of tea, and you had the opportunity to do that there.

When I got to Headley Court, my goal was that I wanted to walk at the Medals Parade. The guys were due to come back from Afghanistan in March 2008. There’s then a six-week leave period, and then everyone comes back to the Unit with their families, and they’re presented with their medals. I didn’t want any sympathy from anybody, I wanted to try and make people proud. So I worked as hard as I could and for as long as I could every day. On the day, I managed to walk with the help of a walking stick, stand with the guys and get my medal presented to me. That day will never leave me, not just because I achieved a goal, but also because my medal was presented to me by my Sergeant Major from Afghanistan. He was heavily involved in my evacuation, and that meant a huge amount to me. It was a fantastic day.

When it came to getting my prosthetic legs, there were no other guys missing three limbs that I knew about in the UK. I needed a mentor in the same situation— someone who was doing better than me, who had been injured longer than me and knew more about this lifestyle than I did. And I found that over in the States, in a young guy named Cameron Clapp. We got in contact, I spoke to the prosthetics team that he worked with and we arranged a date for me to go over and meet him. I spent three weeks training with Cameron, just absorbing all the knowledge he gave me. It changed my life. The things he does are incredible and he’s a huge inspiration to me. We still keep in contact now and have a bit of banter. That focuses me to keep on pushing things.

I’ve adapted my lifestyle in so many ways to compensate for my injuries. I know walking around all day, every day, without using a wheelchair takes its toll on my back and my hips, so I tailored my lifestyle to put the least amount of impact on my body. I cut down on drinking and partying, I slimmed down, changed my diet—just leading a healthier life so I can get more out of it. There’s no getting away from the fact that when I’m older, I’m going to be wheelchair-bound, so I’ve got to live as much as I can before that happens.

It is irritating that people avoid me when I’m walking down the street. I see a lot of parents in the distance, the kid will see me before the parent does and then their parent will see me, and they’ll drag the kid off and veer away from me. They don’t want their kid to ask questions, they think that will embarrass me. But I wear shorts and a T-shirt every day—if I was embarrassed I wouldn’t come out, I’d wear a long- sleeved jumper with a pair of trousers. But there are also a lot of people who are completely different; they ask me what’s happened and they appreciate the honesty

with the children, because the children have to know. There’s no shying away from it, especially now there are a lot of us with missing limbs around the country. We don’t sit in the house, we don’t shy away, the lads are out there doing all sorts of crazy stuff—living their lives every day. Proud of their prosthetics and what they’re doing. People shouldn’t shy away from that.

I left the Marines in July 2010. From the September, I started working for the Royal Marines Association as a welfare operations assistant. It’s a charity that looks after veterans and what we call the wider Royal Marine family—wives, girlfriends, sisters, brothers, mums. I also started a secondary career as a motivational speaker. I travel the country and sometimes the world telling my story to people, hoping to motivate them. I talk a lot about overcoming adversity and goal-setting, which was important to me in rehab. That’s the sort of stuff I love doing.

I am now married to Becky with a little boy and another baby on the way. There are only certain things I can do with the kids, which can be hard. A lot of that is for their own safety—I can’t walk around carrying a newborn, for example, in case I trip or fall. But we still go out, go shopping and have family days out. My daughter’s now eight. She was three when I first saw her after getting hurt. She doesn’t remember me before, so to her, I’m just normal. I’m actually doing an assembly at her school this week. I remember from the moment I was wounded, my fear was that, if I ever turned up at the school, she might get bullied. She doesn’t get bullied, but she gets upset when people ask the same questions again and again. I’m going to address the whole school, answer all the questions that she gets asked, so she can have a bit of a better time at school.

Even though I’ve done talks all over the world, I’ve never been as nervous as I am about going to my daughter’s school. I want to do it so well that when I leave, the kids think she’s a hero, and they all want to be her friend. You know, so she comes out feeling really good about it. I really want to make sure I do a good job and make her proud.